Alternative names for paraganglioma

Extra-adrenal phaeochromocytoma

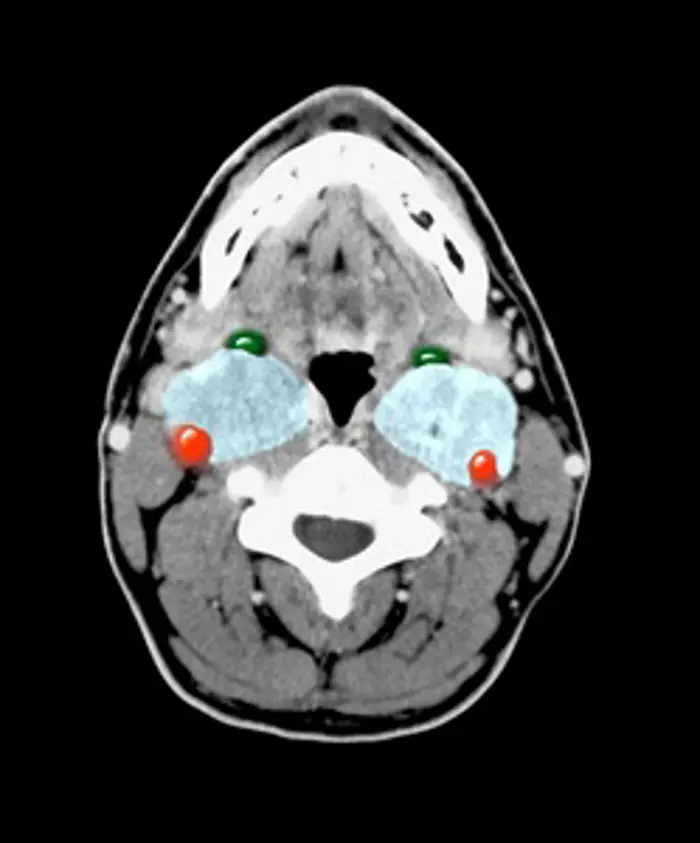

CT image showing masses (paragangliomas) in both sides of the neck.

What is a paraganglioma?

A paraganglioma is a rare type of tumour that forms in the peripheral nervous system (part of the nervous system outside the brain and spinal cord), which is divided into the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. The peripheral nervous system is involved in a variety of important body functions, including controlling blood pressure, heart rate, intestinal movements, and urination. Paragangliomas occur most commonly in the abdomen but can also occur in the neck and chest. They are related to tumours of the adrenal medulla (the centre of the adrenal glands), called phaeochromocytoma. A paraganglioma may be benign (not cancer) or malignant (cancer).

What causes paragangliomas?

It is unclear why paragangliomas occur. However, in some cases, changes in certain genes (called mutations) increase the chance that someone may develop a paraganglioma.

What are the signs and symptoms of paragangliomas?

In many cases, paragangliomas may not cause any symptoms and are found when a test or procedure is done for another reason. Sometimes they can cause signs and symptoms when:

They grow large enough to press on other organs or spread to other organs. For example, if the tumour has spread to the bones, this may cause bone pain. In the neck (carotid paraganglioma), they may be visible as a swelling or compress nearby nerves such as the vagus nerve. A type of paraganglioma (glomus paraganglioma) in the middle ear may lead to hearing loss or hearing a ringing/buzzing sound (called tinnitus).

They release hormones called catecholamines into the bloodstream. Adrenaline and noradrenaline are two types of catecholamines. The release of these extra catecholamines into the blood can cause sweating, a racing heartbeat, feelings of anxiety, headache, and high blood pressure. These symptoms can be similar to panic attacks. These signs and symptoms may occur at any time or be brought on by certain events, such as intense physical activity, having an operation or childbirth.

How common are paragangliomas?

Paragangliomas are rare. It is estimated that two people out of every one million people have a paraganglioma. They can occur at any age, but are diagnosed most commonly between 30 and 50 years old.

Are paragangliomas inherited?

About one in four paragangliomas are inherited as part of familial paraganglioma syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome or neurofibromatosis. Abnormal changes in genes such as succinate dehydrogenase sub-units B (SDHB), C (SDHC) and D (SDHD) are known to be linked to familial paraganglioma syndrome. Mutations in the RET gene are also genetic causes of a paraganglioma.

The inherited forms of paraganglioma are more likely in people with:

- a younger age at diagnosis

- family history of adrenal or kidney tumours

- family history of phaeochromocytoma

- sudden unexplained death at an early age.

How are paragangliomas diagnosed?

Most tests for paragangliomas are done as an outpatient. To look for evidence of increased adrenaline or noradrenaline secretion, patients may be asked to collect their urine over 24 hours or to have a blood test. Computerised tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the body are used to look for paragangliomas and any evidence of spread to other places in the body.

Specialised nuclear medicine scans such as the metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) or positron emission tomography (PET) scans are also sometimes used to identify paragangliomas and any evidence of spread.

A blood test to look for certain gene changes may be taken. This is to identify the risk for having an inherited syndrome and other related cancers. These are usually done in outpatient clinics by genetic specialists, who will talk through the implications of the genetic testing and what a result may mean for the relatives of the patient.

How are paragangliomas treated?

Paragangliomas are usually removed by surgery. The surgery takes place as an inpatient in specialist hospitals. A special period of preparation may be required just before surgery to ensure the blood pressure is well controlled and does not rise or fall excessively. This may include admission for three days or so before the operation for administering intravenous fluids and blood pressure medications.

If a paraganglioma has spread to places where it is not possible for surgery to remove the tumours (e.g. to the liver or the bones), nuclear medicine treatments such as radioactive MIBG or octreotide may be used to slow down the growth of the tumours. This treatment will usually be given as an inpatient in specialist hospitals.

Blood pressure medications (for example phenoxybenzamine, doxazosin or propranolol) are often used to block the effects of excess adrenaline or noradrenaline on the body in order to reduce and control the blood pressure. This may be given as tablets as an outpatient or as an injection in hospital.

Are there any side-effects to the treatment?

After surgery, the patient’s blood pressure will be monitored to ensure it does not rise or fall excessively. Otherwise, this can lead to an increased risk of heart attack or stroke. The side-effects of surgery can include excessive bleeding, infections, pain and possible damage to any surrounding structure (solid organ, blood vessels etc.) around the paraganglioma.

Nuclear medicine treatments do not usually cause side-effects, but, if many treatments are given, this may cause the bone marrow to stop producing blood cells. This can cause a lack of red blood cells which carry oxygen, or a lack of white blood cells which protect against infections. However, patients given these treatments will be carefully monitored for signs of these side-effects.

The blood pressure medications can cause a very low blood pressure, which may cause fainting and feeling dizzy, particularly when standing up. Some of the medications may also cause a slightly stuffy nose and coldness of the hands and feet. In men, phenoxybenzamine may cause absent ejaculation.

What are the longer-term implications of paragangliomas?

Paragangliomas are usually slow-growing tumours. The outcome depends on whether they are benign or malignant and how far the tumour has spread. However, it is possible for patients with treatment to live for many years beyond their original diagnosis.