ESS

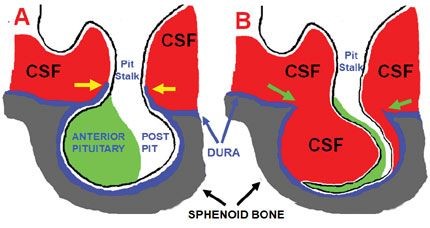

Empty sella syndrome is a rare disorder characterised by the malformation or absence of pituitary gland in sella turcica. The sella turcica is a saddle-shaped depression located in the bone at the base of skull (sphenoid bone), in which resides the pituitary gland. In empty sella syndrome, the sella turcica is either partially filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with a very small pituitary gland lying in the floor of the sella, or completely filled with cerebrospinal fluid with no visualized pituitary gland (completely empty sella).

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of a normal brain, the pituitary gland would normally almost fill the sella turcica. The pituitary gland usually continues to function normally, but in a minority of cases, it can become underactive (hypopituitarism). Hypopituitarism means deficiency in some or all hormones secreted by pituitary gland.

Empty sella syndrome can be due to primary or secondary causes. Primary empty sella syndrome occurs in people who have a weakness in the membrane (diaphragma sellae) that normally covers the pituitary gland. Cerebrospinal fluid is the fluid that flows around the brain. As a result of the weakened membrane, this fluid can leak into the sella turcica and apply pressure on the gland. This can lead to either a flattening of the pituitary gland or expansion of the sella turcica, giving the appearance of an empty sella.

In secondary empty sella syndrome, the pituitary fossa becomes empty because the pituitary gland has been removed through surgery or shrunk through radiation treatment or because of bleeding in to the pituitary gland which is called pituitary apoplexy.

Most people with empty sella syndrome do not have symptoms and it is often only detected when brain scans are undertaken for other reasons. A minority of people may experience headaches or disturbed vision. Deficiency in the production of one or more pituitary hormones (hypopituitarism) is present in less than 10% of people with primary empty sella syndrome, but is more common in those with secondary empty sella syndrome. See the article on hypopituitarism for further information.

Evidence from brain imaging techniques suggests that some degree of primary empty sella is common in the normal population and it is more frequently seen in women than men. Pituitary hormone deficiency (hypopituitarism), however, is only present in a small minority of such individuals.

Secondary empty sella syndrome only affects people who have already had treatment for a pituitary disorder. It affects both genders equally.

Empty sella syndrome is not inherited.

Empty sella syndrome is diagnosed on computerised tomography (CT) or MRI scans of the pituitary area or brain. It is often identified coincidentally whilst carrying out investigations for other reasons. The patient is investigated as an outpatient. Blood tests are also carried out to make sure the pituitary gland is functioning properly and to check for hormonal deficiencies.

Patients with empty sella syndrome who have no symptoms, and with no hormonal dysfunction, do not require any specific treatment. If the patient is deficient in one or more hormones, hormone replacement treatment may be required (see the article on hypopituitarism).

Normal pituitary hormone replacement treatment is not usually associated with any side-effects (see the article on hypopituitarism).

Individuals with normal pituitary function require occasional long-term follow-up. Patients needing pituitary hormone replacement treatment require the same management as other patients with hypopituitarism.

Pituitary Foundation may be able to provide advice and support to patients and their families dealing with empty sella syndrome.

Last reviewed: Jan 2022