Alternative names for gigantism

Pituitary giant; acromegaly of childhood-onset

What is gigantism?

Enlargement of the feet due to pituitary hyperfunction (gigantism).

Growth hormone is an important hormone, made by the pituitary gland. It regulates growth during childhood by promoting bone growth directly and helping to control metabolism.

Growth is a relatively stable process during childhood until puberty is reached. During puberty, sex hormone secretion (oestrogen in females and testosterone in males) increases significantly and causes the growth plates (called epiphyses) found at the ends of long bones to slowly close (fuse) together. Height growth stops at the end of puberty when the growth plates have completely joined.

Gigantism is a rare endocrine disorder caused by unusually high growth hormone levels during childhood and adolescence before the growth plates in the bones have closed. The excessive amount of growth hormone accelerates the growth of muscle, bones and connective tissue leading to an abnormally increased height as well as a number of additional soft tissue changes. When left untreated or uncontrolled, some individuals suffering from gigantism have grown in excess of eight feet (2.43 m) tall. The most well-known example of a person with gigantism is Robert Wadlow, the tallest person in history at 8ft 11 in tall (2.71 m).

Gigantism is very similar to acromegaly. Acromegaly is also caused by excess growth hormone secretion. However, acromegaly happens during adulthood rather than childhood. Height remains normal because the growth plates have fused before excess growth hormone secretion occurs, so long bones can’t grow longer.

What causes gigantism?

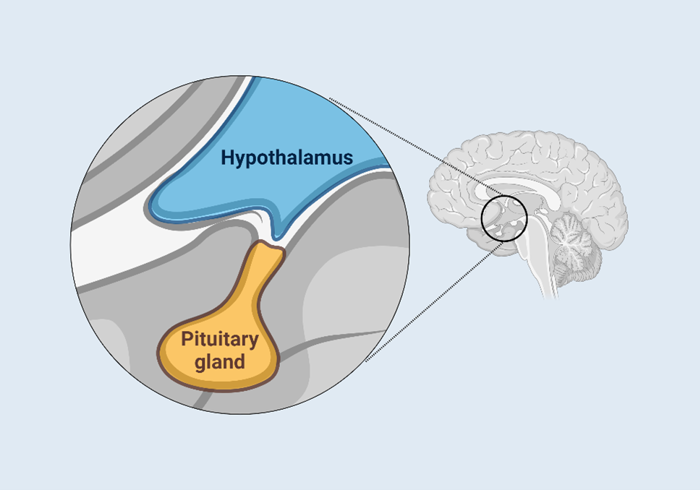

Location of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain.

Gigantism is usually caused by a non-cancerous tumour in the pituitary gland (called a benign adenoma) that produces too much growth hormone.

Pituitary tumours can be small in size (micro-adenoma) or large (macro-adenoma). However, in gigantism, they are frequently large and compress or invade nearby brain tissue. The size of the adenoma directly affects the signs and symptoms experienced by the individual (see below).

What are the signs and symptoms of gigantism?

The signs and symptoms of gigantism are usually due to the excessive amount of growth hormone production and sometimes due to the pressure that larger adenomas may have within or in the brain areas close to the pituitary gland.

The excessive amount of growth hormone can lead to:

- Tall stature, above the expected average for their age.

- Change in facial features such as prominent forehead and jaw, new spaces between the teeth.

- Large hands and feet with thickening of the fingers and toes.

- Excessive sweating

- Aches and pains in the joints

- Tingling in the hands due to carpal tunnel syndrome (squashing of the median nerve in the wrist due to soft tissue swelling from high growth hormone levels).

- Soft tissue swelling

- Enlargement of internal organs, especially the heart.

- Changes in metabolism leading to mild/moderate obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

A larger pituitary adenoma pressing in surrounding areas can also cause:

- Headaches

- Problems with the vision due to pressure on the nerves to the eyes.

- Damage to the rest of the pituitary gland causing failure to produce other hormones (hypopituitarism). If there is a failure of sex hormone production this can cause delayed puberty.

How common is gigantism?

Gigantism is an extremely rare condition, which most endocrinologists may come across only a couple of times in their whole careers. Only approximately six new cases occur each year in the United Kingdom.

Is gigantism inherited?

Gigantism is generally not inherited. There are, however, a number of rare conditions associated with gigantism such as McCune Albright syndrome, neurofibromatosis, Carney complex and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and 4. Gigantism seen in these conditions is still rare.

Recently, a new possible cause of pituitary tumours in families has been suggested, particularly tumours secreting growth hormone or prolactin. These often occur at a relatively young age and are thought to be caused by a genetic mutation.

How is gigantism diagnosed?

If gigantism is suspected, the diagnosis is usually confirmed by taking blood tests to measure the levels of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) circulating in the blood. IGF1 is released into the blood by the liver in response to growth hormone.

An oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) may also be performed. This involves having a glucose drink followed by blood samples taken periodically over two hours to estimate the growth hormone level. Normally, the amount of growth hormone in the blood falls after a glucose drink. However, if a person suffers from gigantism, the growth hormone level remains high.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is undertaken to assess the size of the pituitary gland and the degree of compression of surrounding structures.

How is gigantism treated?

Surgery is the recommended treatment in gigantism. If there is pressure on the nerves to the eyes, this can be relieved and vision improved. In most cases the operation is performed via the nose. Surgery offers a possible cure for acromegaly in the majority of patients.

In cases where surgery is not possible or has not been successful, gigantism may be treated with monthly injections that reduce the release of growth hormone from the pituitary gland. The injections can also sometimes control the size of the pituitary tumour. These are called somatostatin analogues (octreotide and lanreotide). There is also a daily injection of pegvisomant, which stops growth hormone having an effect on the patient's body. Tablets, known as dopaminergics, can also be given. These tablets (cabergoline, quinagolide and bromocriptine) lower growth hormone levels. In general, the injections are much more effective than the tablets and the endocrinologist will monitor the response to treatment with blood investigations and scans.

Radiotherapy may be recommended when surgery has not been possible or has not been effective. This does not mean that the patient has a malignant tumour or cancer. It involves the patient having a Perspex mask made of his or her face and attending hospital for radiotherapy usually for five days per week, for five weeks.

Are there any side-effects to the treatment?

Pituitary surgery can lead to a reduction in the levels of other hormones normally produced by the pituitary gland (see the article on hypopituitarism for further information). All patients will have their pituitary hormone levels monitored after surgery. Replacement treatments are available to restore hormone levels to normal. Other complications of surgery can include excessive bleeding, infection and abnormal sodium levels.

The medical treatments have a number of side-effects, which are usually mild. Somatostatin analogues may cause stomach upsets, diarrhoea and, rarely, gallstones. The dopaminergics can cause loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and dizziness. Pegvisomant can disturb the liver function and regular blood tests are used to monitor this. The endocrinologist will explain these fully and change the treatment depending on the response in order to limit any side-effects.

Radiotherapy lowers growth hormone levels over a number of years and prevents the growth of the pituitary tumour. In a significant number of people, it will also lead to a fall in the production of other pituitary hormones. This will be closely monitored by the endocrinologist who will be able to replace any hormones that are lacking. Short-term side-effects – such as blurred vision, headaches and lethargy – may also occur. Patients should discuss any concerns with their doctor or specialist.

What are the longer-term implications of gigantism?

Following the diagnosis of gigantism, regular, long-term follow up by an endocrinologist is needed to monitor hormone levels (both growth hormone and IGF1). This helps to detect any tumour growth and screening for complications that might have occurred.

Some of the long-term complications that some people might experience relate to the excessive height and overall effects on soft tissues and internal organs. For example:

- Mobility problems due to muscle weakness

- Osteoarthritis

- Peripheral nerve (nerves supplying your hands and feet) compression

- Breathing problems such as sleep apnoea

- Heart such as a larger heart with valve issues

- Metabolic complications such as diabetes.

Practical, daily tasks such as buying clothes, shoes, furniture made for “average-size people” can also diminish the quality of life and this may contribute to some psychological issues observed in this group of patients.