Alternative names for acromegaly

Endocrine growth hormone secreting adenoma; somatotrophinoma

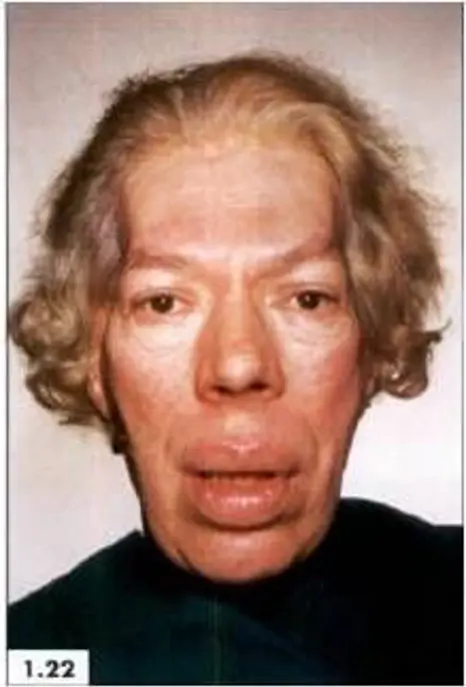

Images above show features of acromegaly – prominent ridges above the eyes and protruding jaw, nasal bone and enlarged lips.

What causes acromegaly?

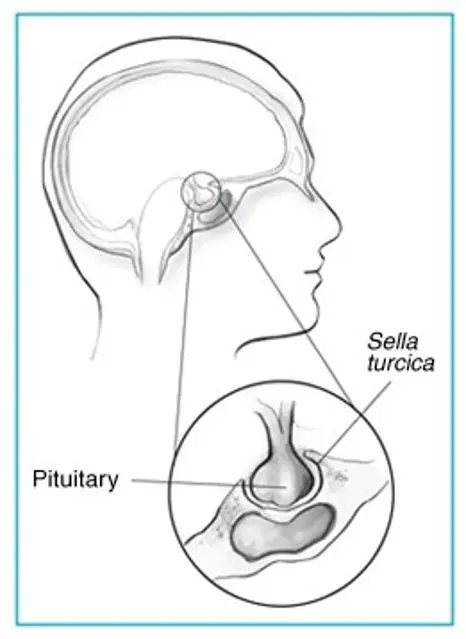

Acromegaly comes from Greek words, which literally mean enlargement (‘megaly’) of the body’s extremities (‘acro’). Acromegaly can develop at any age but is usually seen in adults between ages 30 to 50 years. The excess Growth Hormone (GH) secreted by the pituitary adenoma leads to an increase in the size of the hands and feet, thickening of the skin and a change in the appearance of the face as demonstrated in the pictures above.

In contrast, when secretion of excess growth hormone occurs in children before they have stopped growing, too much growth hormone will result in gigantism where they become very tall because GH promotes growth of arms and legs. In adults, since the growth plates of the bones have fused, it leads to thickening of soft tissues in the hands and feet, and enlargement of the internal organs, but can no longer affect height. Growth hormone also has effects on metabolism, so the patient might also have abnormally high glucose levels or diabetes mellitus.

What are the signs and symptoms of acromegaly?

Symptoms of acromegaly often develop gradually over many years. Symptoms are due to both the excess amount of GH produced and from mass effect of the tumour itself, which can result in changes in vision and headaches.

Early symptoms may include excess sweating, fatigue, weakness, and coarse thick oily skin.

People with acromegaly may notice swelling of hands and feet that can lead to increasing shoe and ring size. Some people may experience numbness and pain in the hands, particularly around the thumb. This happens when the nerves that supply the hands get trapped in the thickened tissues and is called ‘Carpal Tunnel Syndrome’.

Overgrowth of bone and cartilage can cause arthritis and joint pains. Bone changes may alter the facial appearance by protrusion of eyebrows, nasal bone, prominent jaw and forehead. Change in the appearance can be seen when comparing photographs over the years.

Signs in the mouth may include spaced out teeth, enlarged lips, sinuses and tongue. Thickened vocal cords may result in deepening of voice and obstruction of airway could lead to snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA).

Changes in vision such as blurring and headaches occur when the tumour compresses the nerves to the eyes and surrounding structures in the brain.

People with acromegaly can also suffer from high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes and arthritis. Excess growth hormone can also affect the reproductive system resulting in irregular periods and reduced libido in both men and women. High blood pressure and diabetes tend to improve when acromegaly is treated.

How common is acromegaly?

Acromegaly is a rare and gradually progressive disorder. The recent reports suggest it affects 6 per 100,000 people.

Is acromegaly inherited?

Typically, acromegaly is not inherited. Very rarely, acromegaly is inherited in either a condition called 'familial isolated pituitary adenoma' or as part of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN; see the article on MEN1 for further information).

Recent research has identified a small number of families in whom acromegaly has been inherited. This inherited form of acromegaly has been given the name ‘familial isolated pituitary adenoma’. If someone has the gene for this condition, they are more likely to develop pituitary adenoma(s) and release excess growth hormone when they are teenagers, rather than when they are older. As a teenager, the extra growth hormone makes patients very tall because it occurs when the bones are still able to grow (gigantism).

How is acromegaly diagnosed?

Based on the clinical signs described above, your doctor will do some blood tests. GH levels and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) are often elevated in acromegaly. However, GH secretion is in spurts and the results can vary depending on when it is measured.

To confirm the diagnosis, a test called an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is performed, where the patient is given a sugary (glucose) drink. This would normally lower GH levels in healthy individuals, however in patients with acromegaly, this suppression of GH levels does not occur. IGF-1 levels are also elevated in acromegaly, which is a sign of excess GH activity. At diagnosis, the endocrinologist (doctors who specialises in hormones) will also ensure that all the other hormones produced by the pituitary gland are also working normally.

In addition, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pituitary gland is used to locate and evaluate the size of the tumour.

A visual field assessment called visual field perimetry is carried out to check if the patient’s vision is affected, as this tumour can cause pressure on the optic nerves which pass very close to the pituitary gland.

How is acromegaly treated?

Treatment options include surgery, medical treatment and radiotherapy. The primary aim of treatment is to relieve pressure symptoms caused by the tumour and to normalise GH levels and preserve normal pituitary function.

Surgery is recommended in most people with acromegaly, although in some people medical treatment is given initially to reduce the size of the tumour. If there is pressure on the nerves to the eyes, this can be relieved and vision improved. In most cases the operation is performed though the nose (Trans-Sphenoidal Surgery) and the surgeons can access the tumour without having to operate on the main part of the brain. In most patients, surgery is successful and offers a possible cure for acromegaly, however in some cases, not all of the tumour could be removed and further treatment may be required.

In cases where surgery is not possible or has not been successful, acromegaly may be treated with radiotherapy (radiation). This does not mean that the patient has a malignant tumour or cancer. The therapy will be planned and carried out with extreme care and with very low doses of radiation. It may take many weeks to months and while you are waiting you receive drug treatment to suppress GH levels.

Drug treatment is used to inhibit GH secretion from the tumour and are administered as intramuscular injections. Some examples are Somatostatin analogues such as Octreotide and Lanreotide. There is also a drug called Pegvisomant, which blocks the receptor for growth hormone and therefore reduces IGF-1 levels. Oral medications, dopamine agonists such as Cabergoline and Bromocriptine are also widely used to lower GH levels. In general, the injections are much more effective than tablets and the endocrinologist will monitor the response to treatment with blood investigations and scans.

Are there any side-effects to treatment?

After a successful treatment, the patient will start noticing gradual improvement of symptoms. It may take some time return to normal.

Pituitary surgery can lead to a reduction in the levels of other hormones normally produced by the pituitary gland (see the article on hypopituitarism for further information). All patients will have their pituitary hormone levels monitored after surgery. Replacement treatments are available to restore hormone levels to normal. Other complications of surgery can include bleeding, infection and abnormal sodium levels.

The medical treatments have several side-effects, which are usually mild. Somatostatin analogues may cause stomach upsets, diarrhoea and, rarely, gallstones. Dopamine agonists can cause mood changes, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and dizziness. Pegvisomant can disturb liver function and regular blood tests are needed to monitor this. The endocrinologist will explain these fully and change the treatment depending on the response in order to limit any side-effects.

Radiotherapy lowers growth hormone levels over a number of years and prevents the growth of the pituitary tumour. In a significant number of people, it will also lead to a fall in the production of other pituitary hormones (hypopituitarism). This will be closely monitored by the endocrinologist who will be able to replace any hormones that are lacking.

What are the longer-term implications of acromegaly?

In patients who are treated at an early stage (and who have smaller tumours), growth hormone levels could be returned to normal levels. In these individuals there may be no long-term implications, although follow-up should be continued to detect any recurrence.

Certain features of acromegaly may not be reversible for example, changes in the shape of bones and obstructive sleep apnoea. Other problems that affect the quality of life of people with acromegaly include arthritis, which can be progressive, and the fact that there is a possible increased risk of heart disease and sometimes bowel tumours. Because of these problems, patients who have had acromegaly need regular screening.

Are there patient support groups for people with acromegaly?

The Pituitary Foundation may be able to provide advice and support to patients and their families dealing with acromegaly.