The environment in which a baby develops is not only important for its survival at birth but also for its long-term health. During pregnancy, it is important for the baby to receive the correct amount of nutrition, via the placenta, and for it to grow to an appropriate size. The baby communicates its changing nutritional needs and the mother’s body responds to this accordingly. This conversation between mother and baby is spoken in the language of hormones.

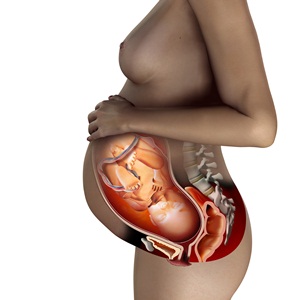

Computer artwork showing a full-term fetus in the womb.

Several different hormones carefully regulate the growth of the foetus during pregnancy. Some hormones promote growth, while others have the opposite effect. It is vital that the balance of these hormones is correct so that foetal growth occurs at a suitable pace throughout pregnancy. Hormones act to prevent foetal overgrowth and undergrowth by carefully controlling the supply of nutrients that pass across the placenta. The placenta acts as an interface between the mother and baby allowing regulated passage of oxygen and nutrients to the foetus. The placenta also produces and responds to hormones that regulate foetal growth and development.

If a baby is born either too large or too small (growth restricted), it can put the mother and their baby at greater risk of certain complications. Larger babies often cause during childbirth (called obstetric problems) such as shoulder dystocia. This occurs during labour when following delivery of the baby’s head, one of the shoulders becomes stuck behind the mother’s pubic bone. This results in a difficult labour in which significant medical intervention (possibly emergency caesarean section) is needed. Babies that are born larger or smaller are at a greater risk of developing health problems later in life, such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, and heart diseases.

, which is best known for regulating blood sugar levels, stimulates foetal growth and a lack of this hormone can lead to a growth restricted (smaller) baby. The primary sugar (glucose) that circulates in blood provides energy for a growing baby, which unlike its mother, is not able to make glucose for itself. The mother will have to supply all the glucose the baby needs for processes like tissue growth and laying down fat. During pregnancy, the mother’s body becomes less sensitive to the effects of insulin and so excess glucose is present in the maternal blood. This is available for passage across the placenta, but the foetus also produces insulin; so when glucose passes across the placenta, insulin stimulates its uptake into foetal tissues allowing it to be used as an energy source. This, in turn, allows tissue growth, or the glucose is converted and stored as fat. By keeping the foetal blood clear of glucose, foetal insulin stimulates the placenta to allow more glucose to pass to the foetus.

Some women can experience a type of diabetes that develops during pregnancy and goes away after birth, known as gestational diabetes. Insulin, like all hormones, works by binding to receptors on target tissues in the body, much like a key fits a lock. In gestational diabetes, the receptors that insulin normally binds to do not work properly and glucose is not cleared out of the mother’s blood. This leaves too much glucose in the mother’s blood, which passes across the placenta to the foetus. This increase in glucose passing to the foetus can lead to increased fetal growth and a bigger baby. Overweight and obese women are more likely to suffer with gestational diabetes than normal weight women, but this problem can be managed by limiting weight gain during pregnancy with careful exercise and healthy eating habits. In cases were healthy eating and exercise is not sufficient to treat gestational diabetes, medication (primarily metformin), which reduce glucose levels, can be used.

The insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) are a family of hormones with a similar action to insulin, and like insulin, they also play a key role in foetal growth during pregnancy. Insulin-like growth factors are also known as ‘growth factors’ as they both stimulate the growth and survival of the foetus.

There are two main types of insulin-like growth factor – IGF-I and IGF-II. Some studies have shown that the higher the level of IGF-I in foetal blood, the greater the foetal weight at birth. Not enough IGF-I during pregnancy results in a smaller baby, which may struggle to grow after birth. However, cases of this are very rare and are usually a result of a genetic disorder. In normal pregnancy, IGF-I is thought to act as a ‘nutrient sensor’ checking which nutrients are present and how much of them are available, and then matching this to foetal demand. This is significant because the different types of nutrients the baby receives can be just as important as the overall amount. IGF-I is central to this effect because it can alter the passage of nutrients across the placenta, varying the amount and speed of transfer of the different types of nutrients, in response to changing foetal demand. The ability of IGF-I to change placental transport of nutrients can also be used to counteract the effects of under-nutrition; if the foetus is not getting enough nutrition to grow properly, IGF-I is able to sense this and increase the amount of nutrients passing across the placenta.

IGF-II helps the foetus grow by stimulating the growth of the placenta and allowing more nutrients to pass to the foetus. If there is a lack of IGF-II, placental growth and placental function are compromised. This can result in a smaller baby as it may not receive all the nutrition required during pregnancy. If too much IGF-II is present, it can lead to foetal overgrowth and a larger baby; however, this is a rare occurrence and is only usually seen in genetic disorders, such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.

The insulin-like growth factors work together to stimulate and control foetal growth via changes in size and function of the placenta. IGF-II is important for placental growth and development, whereas IGF-I finely tunes what passes across the placenta. This means IGF-I levels respond to changes in both the maternal environment and foetal demand, ensuring the growing baby is supplied with everything it needs.

Other hormones, such as the steroid hormones corticosterone and cortisol, are important for foetal development during pregnancy. These steroids belong to a family of hormones, called glucocorticoids, which are known to be associated with the regulation of stress. Unlike insulin and IGFs, glucocorticoids limit foetal growth and coordinate the development of foetal tissues and organs. As pregnancy nears term, a surge in glucocorticoids produced by the foetus can be detected. This naturally slows foetal growth, in favour of maturing and developing foetal tissues and organs. It is vital that the foetal tissues and organs go through this process at this time, in order for them to function properly outside of the womb. Women in Europe and the USA are given the glucocorticoid dexamethasone if labour begins before 37 weeks of pregnancy - this stimulates maturation of the baby’s tissues and organs (especially the lungs), so even if the baby arrives earlier than expected, the baby should be able to breathe and function outside of the womb. This medical intervention significantly decreases the mortality and morbidity rates of premature babies.

Glucocorticoids change the pattern of foetal development from tissue growth to specialisation; so instead of building the tissues, glucocorticoids help them mature, thus preparing the baby for life after birth. However, if the foetus is exposed to large amounts of glucocorticoids prematurely, the normal pattern of foetal growth is disturbed and foetal tissue development occurs incorrectly, which can have long-term health consequences. Stress triggers the production of cortisol from the mother’s adrenal glands and so high levels of cortisol cross the placenta and result in smaller babies and an earlier birth. This is why pregnant women should avoid stress wherever possible. Studies have also shown that in very stressful situations, such as natural disasters, pregnant women are more likely to have smaller babies that are born prematurely due to the large amounts of cortisol made by the mother. Babies that are born before term, especially if they have a low birthweight, are often less likely to survive after birth and may experience long-term health consequences, such as developmental problems and learning disabilities. Glucocorticoids are therefore vitally important to normal foetal growth and health; however, they must be present at the correct levels and at the correct time to ensure they do not have adverse effects on either the mother or the baby.

The thyroid hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are also essential for normal growth and development of the foetus. Particularly, these thyroid hormones are needed for the development of the baby’s brain. The foetus starts to produce these hormones from around the 16th week of gestation, so before this, the foetus has to depend on the mother’s thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormone receptors are known to be widely distributed throughout the brain of the foetus before it can directly produce these thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormones can also control the availability and effectiveness of other hormones involved in fetal growth, such as IGFs. Not enough thyroid hormone can severely impact the development and can result in an under active thyroid in the baby, known as congenital hypothyroidism, which will need to be treated with thyroid hormone replacement. All babies in the UK are offered a blood test when they are 5 days old to test for congenital hypothyroidism, along with 8 other conditions.

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/baby/newborn-screening/

Last reviewed: Feb 2023